Lecutre 7

We will start be continuing in our answer to the question:

What shapes emerge from beinding energy considerations alone?

Pancake

A pancake is a cylinder with rounded sides.

Let the rounded sides have height \(2r\) and the radius of the enclosed cylinder be \(R\).

For \(R>>r\):

\[\Delta E \approx \pi^2 B \frac{R}{r} \\ V \approx \pi R^2 (2r) \\ A \approx 2 \pi R^2\]Knowing the volume and surface area, we can calculate the reduced volume of the pancake.

\[\bar{V} = \frac{6r}{\sqrt{2} R} \\ \text{let } \rho \equiv \frac{R}{r} \ \Rightarrow \bar{V} = \frac{6}{\sqrt{2}}\frac{1}{\rho}\\ \Delta \bar{E} = \pi^2\rho \\ \bar{V} \approx \frac{6\pi^2}{\sqrt{2}\Delta \bar{E}}\]Doublet

This is a sphere with a smaller sphere growing out of it. It can be thought of as simple model of cell division where a circular cell is being pinched out of another. Let the radius of the large sphere be \(R\) and that or the smaller, pinched sphere be \(r\).

\[V = \frac{4}{3}\pi (R^3+r^3) \\ A = 4\pi (R^2+r^2)\]We can use this to calculate the reduced volume.

\[\Rightarrow \bar{V} = \frac{\rho^3 + 1}{(\rho^2+1)^{3/2}}\]Again, \(\rho \equiv R/r\). Lets examine some limiting cases for different values of \(\rho\).

| $$\rho$$ | $$\bar{V}$$ | |

|---|---|---|

| $$\rho\rightarrow \infty$$ | $$\bar{V}=1$$ | |

| $$\rho=1$$ | $$\bar{V}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}$$ | |

| $$\rho\rightarrow 0$$ | $$\bar{V}=1$$ |

Also note that since we are dealing with two spheres \(\Delta E\) is simply the bending energy of a sphere which is a constant, independent of radius.

\[\Rightarrow \Delta \bar{E} = 4\pi(2B+G)\]Stomatocyte

This shape is the opposite of a doublet. Instead of a sphere growing out from the edge of another sphere, this is a sphere with the volume of a smaller sphere being removed from it. The larger sphere has radius \(R\), and the smaller sphere that is removing volume has radius \(r\).

\[V = \frac{4}{3}\pi (R^3-r^3) \\ A = 4\pi (R^2+r^2)\]Notice that the total volume is the difference rather than the sum of the two spheres whereas the surface area remains the same as that of a doublet. This means that \(\Delta \bar{E}\) is the same as the doublet case and the reduced volume is very similar.

\[\bar{V} = \frac{\rho^3 - 1}{(\rho^2+1)^{3/2}}\]As in the doublet case, lets examine some limiting cases.

| $$\rho$$ | $$\bar{V}$$ | |

|---|---|---|

| $$\rho\rightarrow \infty$$ | $$\bar{V}=1$$ | |

| $$\rho\rightarrow 0$$ | $$\bar{V}=0$$ |

Shape phase space

If we were to plot \(\Delta\bar{E}\) as a function of \(\bar{V}\) we would find a phase space of where different shaped membranes exist. In certain regimes of reduced volume varying shapes are energetically favorable.

However, our arguments breakdown if we examine bacteria instead of ordinary cells. Bacteria are single cell organisms which have a hard cell wall. The phase space does not apply to them since their shape is defined by a much more rigid cell wall.

Bacteria Cell Walls

Bacteria keep thier internal pressure much higher than the external pressure in the environment. This is why they need something much harder than a cell membrane in order to keep their shape intact.

Lets examine the forces a cell wall must sustain for walls of different shapes. In the following examples let the outward pressure the cell wall feels be \(P\) and the thickness of the wall be \(d\).

It is also useful to define the quantities stress and tension.

\[\text{Stress } = \sigma \equiv \frac{\text{Force}}{\text{Area}} \\ \text{Tension } = \tau \equiv \frac{\text{Force}}{\text{Length}}\]Spherical Cell Wall

In the spherical case we can imagine cutting the sphere in half and consider the force \(F\) needed to keep these two halves together.

\[F = \int da \ P \cos\theta \\ da = R^2 \sin\theta \ d\theta \ d\phi \\ \Rightarrow F = \int_0^{2\pi} d\phi \int_0^{\pi/2} d\theta \ R^2\sin\theta \ P \cos\theta \\ F = \pi R^2 P\]And so the stress and tension the spherical cell wall feels are the following:

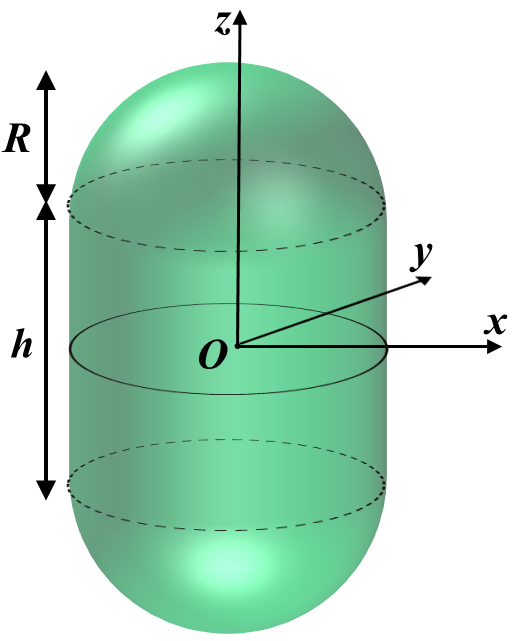

\[\sigma = \frac{RP}{2d} \\ \tau = \frac{RP}{2}\]Spherocylinder

Spherocylinder is a very common shape of cell walls. There are two ways of pulling apart a spherocylinder.

Again, in our notation \(h \rightarrow L\).

- Pulling from either spherical end. This equates to forces pulling in the z-direction. This force will be denoted as \(F_z\).

- Pulling it apart through the z-axis. This equates to equal, opposite forces pushing in the x-y plane. this force will be denoted as \(F_\phi\) since it is azimuthaly symmetric.

\(F_z\) will be identical to that of spherical wall, and so will the stress and tension.

\[\sigma_z^\text{cyl} = \sigma^\text{sph}\]We can calculate \(F_\phi\) by imaging we cut the spherocylinder in half down the z-axis and consider the amount of force it would take to keep the two halves together.

\[F_\phi = \int da \ P\sin\phi \\ F_\phi = \int_0^L dz \int_0^{\pi} d\phi \ R^2 P \sin\phi \\ F_\phi = 2RLP\]And so the stress in the \(\phi\) direction on the cell wall is the following:

\[\sigma_\phi = \frac{PR}{d} \\ \rightarrow \sigma_z = \frac{1}{2} \sigma_\phi\]The stress on the spherical ends of the cell wall are half that of the cylindrical sides.

Written with StackEdit.