Exploring DNA Sequencing Data

In this post I will investigate the sequencing data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) in order to familiarize myself with handling sequencing data. Specifically, I will focus on a dataset which is a subset of somatic mutations found in colorectal cancer patients.

The data I used and my ipython notebooks for this project can be found on my repository.

The data in data_colorectal.txt contains almost a million different somatic mutations with chromosomal positions relative to the human reference hg19. More detailed information on human reference hg19 can be found on the UCSC genome browser.

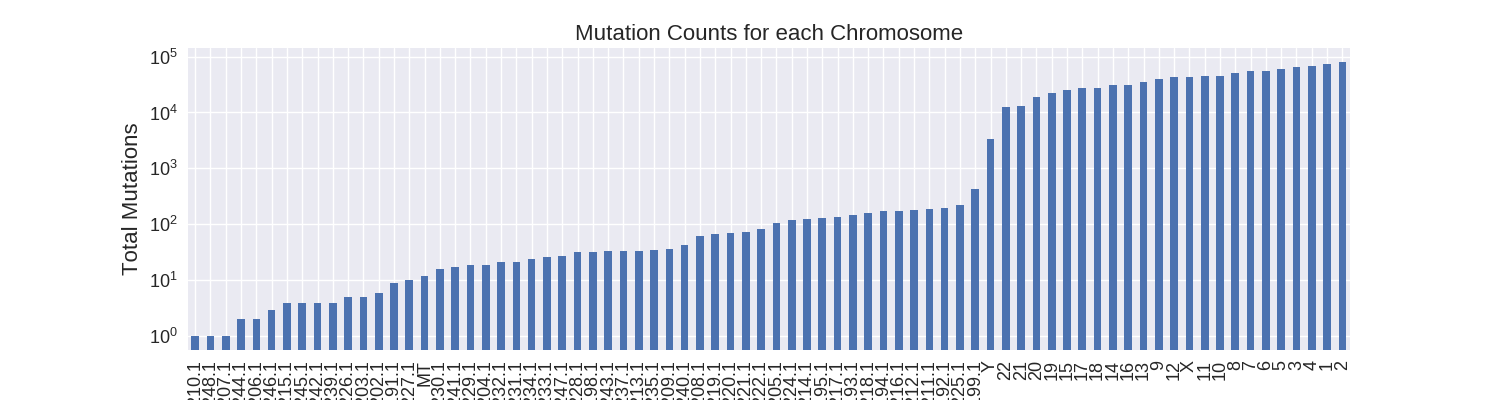

As a first step I decided to focus on how the somatic mutations were distributed across the different chromosomes. There are 76 unique chromosomes in the data: 24 regular chromosomes (1-22, X, Y), mitochondrial DNA (MT), and many unlocalized and unplaced chromosome contigs (GL000191.1-248.1). The most mutations occur in the regular chromosomes with all of them, except for Y, having at least ten thousand mutations.

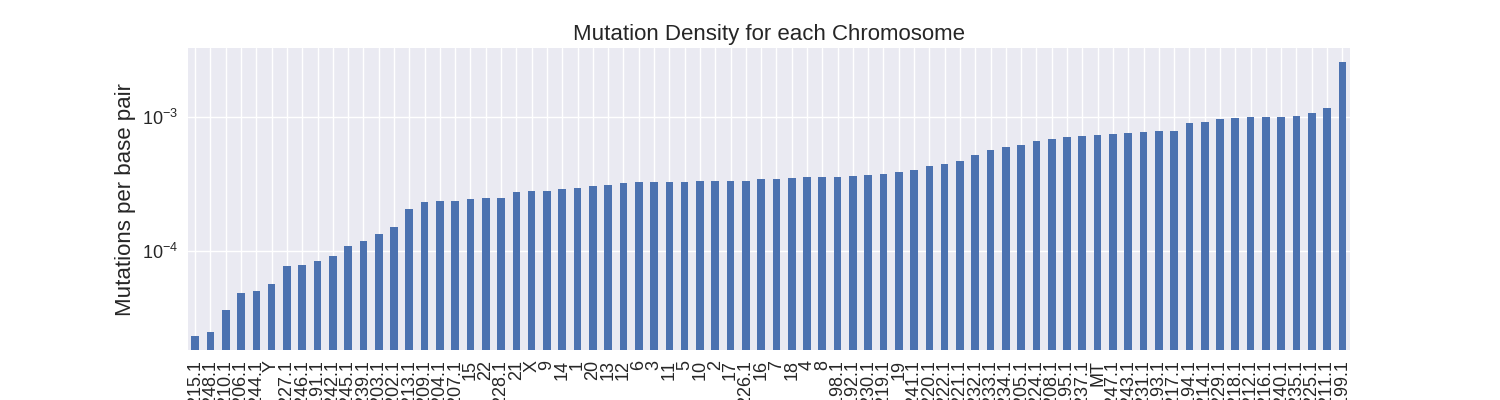

Next, I wanted to calculate the mutation density. Since all the chromosomes are of different sizes, longer chromosomes are predisposed to having more mutations than shorter ones. Calculating the density of mutations eliminates this bias.

In order to calculate the density we must know the size of each chromosome, so I downloaded the data for chromosome sizes of human reference hg19 from the UCSC genome browser.

The regular chromosomes have the largest size and therefore it makes sense that they would also have the highest mutation counts. With the hg19 data I link the chromosome mutations counts to the chromosome sizes in order to calculate their mutation densities.

When calculating the mutation density, I find an average mutation density of about 1 somatic mutation per two thousand base pairs across all chromosomes. All regular chromosomes - except for Y - have over 1 mutation per ten thousand base pairs. The unlocalized and unplaced contigs have much more variable mutation densities due to their smaller sizes.

When calculating the mutation density, I find an average mutation density of about 1 somatic mutation per two thousand base pairs across all chromosomes. All regular chromosomes - except for Y - have over 1 mutation per ten thousand base pairs. The unlocalized and unplaced contigs have much more variable mutation densities due to their smaller sizes.

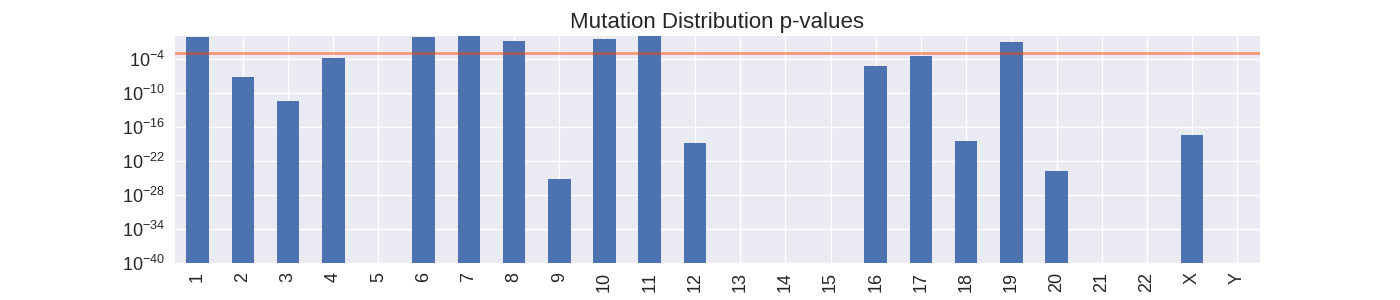

I was also interested in investigating the distribution of point mutation locations in the various chromosomes. The idea here being that in the absence of some driver causing mutations at a particular location in the genome, one would expect that mutations are more or less equally likely to occur anywhere along the chromosome. If mutations from our sample data are distributed in a significantly non-uniform way, then it may be indicative that some particular mechanism (such as cancer) is driving a large amount of mutations at a particular location in the genome.

I quantified non-uniformity by calculating how likely it was to draw the mutation positions of each chromosome found in the data from a uniform distribution. From here we can calculate p-values to signify the probability that the mutation positions sampled did in fact come from a uniform distribution. For this analysis, I focus on my attention on the regular chromosomes since they are functionally more important than the irregular chromosomes as well as having in general the higher highest mutation densities.

Chromosomes with large p-values (bars higher than the orange line) are likely to have their mutations uniformly distributed across the entire chromosome. Chromosomes with small p-values are likely to have mutations distributed non-uniformly.

Chromosomes with large p-values (bars higher than the orange line) are likely to have their mutations uniformly distributed across the entire chromosome. Chromosomes with small p-values are likely to have mutations distributed non-uniformly.

Calculating p-values is quick way of identify chromosomes where mutations are more concentrated than would normally be expected, and so can provide a quick way of identifying locations along the genome that are very high in somatic mutations. A high local density of mutations may be indicative of a particular gene or genetic pathway being targeted by the cancer. However, this method of classifying non-uniformity does have its issues. In the case of classifying chromosome with a small sample of mutations the resulting p-value may be misleading because of the small sample size. Therefore this technique is not practical for picking out low frequency mutations.